I was going to make this a joke guide for April Fools originally, since let’s be honest… who doesn’t know how to take apart a Glock? Whether you think they’re “Perfection™”, a durable utilitarian tool that gets the job done, or an ugly brick of a plastic wonder-nine that will never live up to the hype, the Glock pistol is everywhere. What the Glock lacks in aesthetic appeal it makes up in simplicity, low part count, and ease of tuning. After all, there aren’t many pistols out there that you can do a $10 trigger job on quite like the Glock. Instead of just making the shortest disassembly guide in history, let’s discuss the history of the Glock and some tuning tips to spice things up!

A “Brief” History of Glock

There are many, many comprehensive histories of Gaston Glock and his pistol written by much more knowledgeable folks than myself. The complete history of Glock is colorful to say the least and full of misconceptions, so I absolutely recommend anyone who hasn’t read up on it to do a little digging! Glock himself is an interesting guy, though not wholly responsible for the pistol’s design, and was even the target of a failed conspiracy to knock him off and seize the company. Rather than diving into the intrigue and the politics, I’m just going to summarize the timeline of Glock development and the major generational changes.

Generation 1: The first generation of Glocks debuted with the famous model 17 and shortly after with its infamous videogame and movie featured select fire variant, the model 18. Early Glocks lacked the grip texture or finger grooves of later models and had no rail on the frame for lights or accessories. The upper portion of the grip also lacked the dished out thumb rest prominent on later models, but that’s a more subtle difference. Internally, the first gen guns would remain largely unchanged for three generations except for the addition of the reinforcing pin in the locking block, making the earliest guns “two pin” pistols while later revisions became “three pin”. The frame rails molded into the frame are shorter on the first gen pistols than later models (which led to immediate changes due to mechanical issues) and early models were sold without captive recoil spring assemblies. Early Glock mags weren’t drop free and only contained a partial metal lining for reinforcement.

“Gen 1” Glock 19: While no official generation 1 Glock 19 exists, a number of them were produced by Glock to submit to the ATF for approval in 1987. They were made out of chopped down Glock 17 full size frames with a prototype slide and barrel, and exact numbers of test samples aren’t really known from what I’ve been able to dig up.

Generation 2: Around 1988, Glock revised their smash hit model 17 and introduced the compact model 19 which has since become something of a gold standard in concealed carry sized handguns. A slew of new calibers were added to the line in 1990 and ’91, starting with 10mm Auto, .45ACP and the burgeoning .40S&W. The new generation introduced “grenade checkering” on the front and backstraps of the grip, which stuck around for almost 20 years. The model line branched out further with the 17L long slide model, which would become the basis for future competition models down the line, and the first “C” series pistols incorporating compensated slides and barrels. Glock continued to revise their small parts, including the extractor, striker, striker block plunger and trigger connector, in incremental draw lots that culminated in a large warranty service upgrade in 1991 and ’92 for older guns to receive the newest parts. Revised generation 2 magazines had full metal lining and went through several small changes in the follower, base plate and spring over the years.

Transitional: In a strange case of hybrid features, some sub-compact model 26 pistols from around 1995 to ’96 can be found as a “generation 2.5” configuration with finger grooves that lack the grenade checkering normally present on the front strap. Around the same time, Glock introduced several other models in a “generation 2.5” setup with no accessory rail but textured finger grooves, including the big bore models 20 and 21. The big bore models introduced the reinforcing pin into the locking block, but this became standard on all Glock models going forward.

Generation 3: From about 1997 until 2010, Glock’s third generation became a staple of gun owners in the US. Coupled with the sunset of the Clinton era “Assault Weapons Ban” in 2004 and a huge rise in popularity of practical shooting sports, concealed carry and home defense, Glock enjoyed massive popularity. It was this generation that cemented the Glock 19’s status as a standard carry gun to many buyers, but Glock spent their time expanding their product line in leaps and bounds beyond their most popular models. Along with full production of the sub-compact Glock 26, the company added the new .357 SIG cartridge available in all three of their now-standard sizes: Full, Compact, and Sub-Compact. In 1998 Glock introduced their first big bore subcompact, the Glock 36 in .45ACP, and began producing purpose made competition models patterned after the original 17L.

The two tell-tale signs of a generation 3 Glock are the finger grooves on the front strap and the thumb rest sunk into the top of the grip. All of the incremental updates to small parts were rolled into the third gen pistols, as were full metal lined magazines right from the start, and a new hinged plastic carry case was provided with pistols instead of the tupperware box of previous generations. The big bore pistols would get a branch around 2006-2007 dubbed the Short Frame, which reduced the trigger reach by shrinking the back of the grip and reducing the famous grip hump. Both the full sized 21 and compact 30 would be available as SF models, the latter of which I personally owned and carried for several years.

Transitional and RTF: Prior to the fourth generation official announcement, Glock started rolling out some odd variants of the gen 3 pistols with new experimental features. They released two versions of a new frame texture dubbed Rough Texture Frame, which differed in the actual roughness of the texture itself. RTF1 was the more aggressive treatment, while RTF2 would more or less carry over to become the gen 4 grip texture a year or so later. Glock also debuted the infamous “fish gills” slide serrations to much derision from Glock fans and haters alike, and these oddball pistols have become something of a collector’s item despite being recent production.

Ambi Release: At one point during the third generation, Glock experimented with a true ambidextrous model which also incorporated a 1913 Picatinny style frame rail. This short lived ugly duckling was only available to my knowledge as a Glock 21SF and was discontinued in a matter of weeks or months due to a myriad of issues revolving around the magazine release sticking, dragging, or otherwise failing.

Generation 4: The current generation of Glocks as of the time of writing launched in 2010 with much fanfare. Glock’s new release became a hot topic not because of any new features or the inclusion of a third magazine with new pistol sales, but because of a massive recall issued by the company for faulty recoil spring assemblies. Glock changed the captive, polymer guide rod and flat coil spring assembly they’d been using since 1988 in favor of a telescoping dual spring setup that was billed to reduce felt recoil and improve service life. Instead, early adopters got cycling issues and an offer from Glock to return their pistols for service free of charge. After a few months of firestorm caused by the recall, the issues were solved and the gen 4 pistols are back on track. Later in 2014, the new model 30S finally hit the market in .45ACP and the first .380ACP Glock pistol available in the US launched as the model 42. Competition .45ACP, Modular Optic System, and a 9x19mm single stack model 43 were all added to the catalog under the fourth generation too.

Gen 4 pistols are immediately identifiable by their RTF2 style frame, which replaces the old style pebble texture with a modern pattern of tiny pyramids. The finger grooves are toned down somewhat but still present, and the back of the grip now has provisions for an interchangeable backstrap system to adjust the size of the grip to the shooter. The magazine release has been redesigned into a more prominent and textured button, to the relief of many Glock owners over the years who resorted to cutting the frame hole larger to accommodate jumbo mag releases. Following the awful ambi release 21SF incident, Glock opted to simply design the magazine release to be reversible instead.

Gen 5/”M” or “MHS” Models: There hasn’t been news of Gen 5 at the time of writing, but recently Glock competed against Sig Sauer for military contracts under the Modular Handgun System program and lost to the P320. Photos of the Glock 19 and 23 MHS trials models aren’t especially amazing, but they do highlight a few changes that are noteworthy. The MHS model lacks finger grooves entirely, uses an RTF style texture, and comes equipped with an ambidextrous thumb safety per military request. Unlike the FDE and OD Green commercial pistols, the “M” trials guns were provided in full FDE slide and frame alike, though I don’t know what the slide was coated in. Additionally, in 2016 photos surfaced of a law enforcement only sale Glock 17M, not to be confused with the MHS, which lacks finger grooves but otherwise appears to be a standard 17 Gen 4 without the added thumb safety. Statements by Glock indicate the manual safety MHS pistol will never be released to the commercial market.

Actual Gen 5: Not long after the original publication date of this guide, Glock announced their fifth generation of pistols with a short list of changes to the classic design. Modern features like forward slide serrations, a flared magwell, ambidextrous slide stops and a reversible mag catch are immediately recognizable at a glance. Internally, the trigger connector and firing pin block saw reworks advertising an improved trigger reset. New “Marksman” barrels with more aggressive polygonal rifling also headline the new model rollout.

MOS: The first optic-compatible model Glock arrived at the tail end of Gen 4, becoming a standard feature in Gen 5 with MOS models available for most pistols. The Glock optic plate system has seen mixed reactions and constant debate over Glock’s implementation.

Discontinued in 2014: A major catalog change went down in 2014, when Glock discontinued a bunch of their big bore models and all of the “C” marked compensated barrel models officially. The SF variants of the .45ACP and 10mm models (e.g. the full size 21, compact 30, and so forth) remained in production.

US Production: Glock has actually pushed forward on domestic manufacture of their pistols on several occasions, and it’s entirely possible to find some serial ranges of Gen 3 and now Gen 4 pistols that were built in the USA. The first runs that I know of near the tail end of Gen 3 had a lighter grey slide finish than usual, and their own serial number range unique to those pistols. Oddly, the primary purpose for USA made Glocks is for export, in order to end-around tariffs or countries that block Austrian arms imports.

The Tenifer Scandal: Around 2007, Glock made changes to the slide finish treatment to comply with chemical regulations surrounding one of the primary ingredients of the caustic dip. Their trademarked “Tenifer” process was phased out in favor of Melonite, both of which are similar forms of black nitride over a heat treat process. According to some, the early Melonite had numerous issues with wear and durability that took Glock up to a year to solve. Some Glock buyers swear by the Tenifer name, while others don’t seem to care as long as their gun goes bang.

Manual Safeties: The original Glock design in 1982 was actually provided with a manual thumb safety as an option, but the feature was of course dropped long before production. Some organizations ordered this model, however, but exact numbers aren’t well documented outside of Glock’s own records. The concept would come up numerous times over the past 30 years of Glock production and come full circle with the US military trials models mentioned above. As a side note, noted gunsmith Joe Cominolli developed an aftermarket thumb safety kit which saw some use in the US by police departments

Import Points, Glocks, and “Target Triggers”

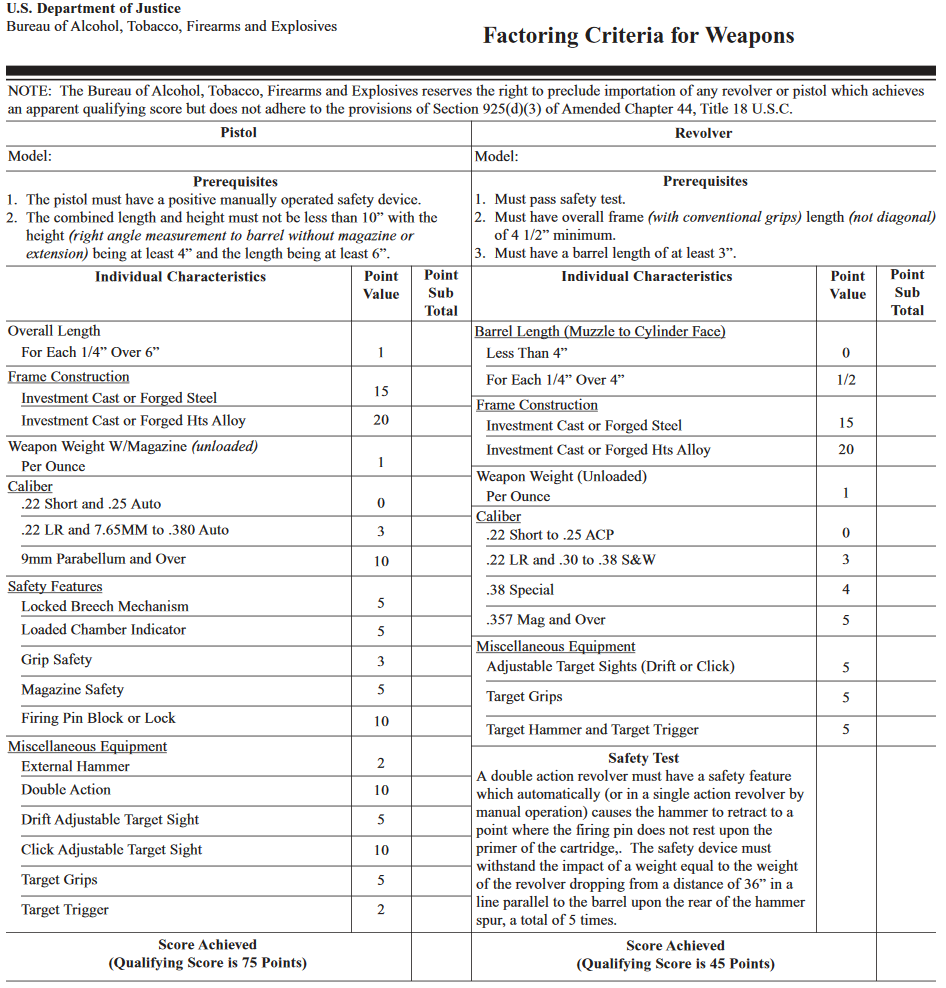

Astute Glock owners may be curious why full sized models like the 21 often ship with a smooth faced trigger, while the compact models are provided with the god-awful serrated trigger instead. The answer is a legal quagmire dreamed up by the ATF called “import points” and designed to dissuade or outright ban inexpensive pistols from importation into the US. On the surface the idea is to keep cheap Saturday Night Special pot metal guns from entering the country, but the table of point values and features is, like most gun regulations, fairly arbitrary. Here’s the actual chart, per the ATF Form 4590 (5330.5):

As you can see, not only do semi-auto pistols have a much higher points requirement but they also have vague line items like a “target grip” or “target trigger” which have no real definition. In Glock terms the target trigger is the serrated type as opposed to smooth, while the target grips are the addition of the finger grooves back in Gen 3. Now you know why the earliest Glock 26 pistols still had finger grooves, despite pre-dating the addition of them on the other models… they needed the extra five points because of the pistol’s small size. The .380ACP models made in the 90s were disqualified because they were simple blowback, which sacrificed the extra 5 points from having a locked breech mechanism.

As you can see, not only do semi-auto pistols have a much higher points requirement but they also have vague line items like a “target grip” or “target trigger” which have no real definition. In Glock terms the target trigger is the serrated type as opposed to smooth, while the target grips are the addition of the finger grooves back in Gen 3. Now you know why the earliest Glock 26 pistols still had finger grooves, despite pre-dating the addition of them on the other models… they needed the extra five points because of the pistol’s small size. The .380ACP models made in the 90s were disqualified because they were simple blowback, which sacrificed the extra 5 points from having a locked breech mechanism.

It’s worth noting that the extractor counts as a Loaded Chamber Indicator from Gen 3 onward after changes in the design, though you can still find and use non-LCI extractors. Another interesting note is that the addition of Click Adjustable Target Sights is a whopping ten points, and Glock does in fact equip their pistols with disposable plastic target sights specifically for importation, then removes them. Even the full size Glock 17 racks up only 70 points, hence the use of the disposable target sights!

The silver lining here is that as you can guess from Glock’s importation process, the import points become irrelevant once the gun is in the country. It’s perfectly safe to swap out your uncomfortable serrated trigger for a smooth faced one. A word of caution, however, if you find yourself packing up your Glock to send it in for service. Chances are, Glock won’t return your smooth trigger on a model that shipped new with a serrated one. Make sure to strip out all of your mods first!

Disassembly Guide

The Glock is so simple we’re not even splitting this up into frame and slide sub-sections. The total part count on the Glock is cited to be 34 components, and the entire gun can be taken down with one small punch and a roll of tape. You’ll need a hex nut driver if you plan on replacing the front sight though; pistols prior to around 2007 have a plastic front sight you can pull out with pliers, but later pistols now use the hex nut screw across the board in my experience.

- Field strip. Clear the pistol, remove the magazine, and dry fire it to let the striker down. Pull slightly back on the slide, less than half an inch is necessary, and pull down the locking lever. Pull the slide off the frame.

- Remove the slide cover. With a punch, pull down on the striker’s plastic sleeve and pull the slide cover down. The sleeve locks into the cover, and the extractor spring and plunger are tucked in there too. All of that comes out.

- Remove and disassemble the striker assembly. Use the slide as a backing to pull the striker spring down and remove the spring cups. Now is the time to experiment with striker spring weights!

- Remove the extractor and striker block plunger. You can do this any time after removing the extractor spring. Push in on the block plunger and the extractor will fall out, since it’s retained in part by the plunger. Pull the plunger out with its spring.

- Knock out the pins. The reinforcing pin at the top (small diameter) is often called the “first pin” since it comes out first and goes back in first. When pushing out the trigger pin (larger diameter one) you can wiggle the slide stop to free it up.

- Lift out the locking block. Use your punch to lever the locking block out from the front. At least that’s how Glock insists you do it. You can grab the slide stop at the same time, since it’s free.

- Lift out the guts. The ejector housing contains most everything else, and lifts right out of the frame.

- Separate out the bits. Pull the trigger bar forward and off its shelf, then unhook the return spring from it. Unhook the other end of the spring from the ejector housing, and push the trigger connector piece out from the back.

- Magazine release. For once an easy mag release! Snag the spring with a pick and maneuver it out of the slot in the mag release to free it up and remove it.

- Slide lock. Just press down on the flat spring and pull the locking lever out. Make sure you reinstall this the correct orientation, with the locking ridge at the top facing backwards.

Reassembly tips: Not a lot to say here, but the one tip that may save you a little hassle is to keep in mind the “first pin” so you can slip the slide stop under it.

Whoops, I tuned something and now I can’t dry fire! Don’t panic, just lock the slide back and use the same procedure to remove the slide cover and striker assembly.

Quick Tuning Tips

I get asked about Glock trigger tuning a lot, and I won’t profess to be a full on Glockmeister by any means. I enjoy working on Glocks, my first two carry pistols were Glocks that I tuned to my liking, but I would be lying if I claimed that working on a Glock is as exciting as overhauling a 1911 down to 3.5#. My methodology for Glock tuning is simple and inexpensive as it gets. You don’t need $25 trigger connectors or $149 drop in kits to get an excellent trigger on a Glock, at least within the realm of concealed carry or practical shooting sports. In my opinion, the best Glock triggers I’ve tuned used only elbow grease and a few bucks in Wolff springs. The spring and polish job is really the foundation of Glock trigger work, so my advice is to try the spring and polish method first and if you need your trigger lighter for competition then you can invest in more parts.

I do see value in the aftermarket striker blocking plungers, since this is a real sticking point for many striker designs in general. A domed and polished striker block changes the feel of the trigger immensely compared to the standard flat topped style, and some pistols I’ve seen (cough FNS cough) have absolutely awful striker block plungers that turn the trigger into a pothole ridden country road. I’m not a huge fan of the titanium nitrided ones, though.

Keep in mind that many of the aftermarket trigger connectors are coated, typically nickel type finish. I’ve encountered quite a few that had uneven finishes or flaking, and of course trying to polish them will remove the finish entirely but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. You can play around with the pre-travel tab connectors if you like, but I’m a fan of the two stage trigger feel so long as the first stage is lightened and smoothed out.

NY Spring: Some people recommend using a light connector with the heavy New York #1 (Olive) trigger spring, which is aimed at making the trigger feel like a light revolver-style double action. Unlike the pull type return spring, the NY springs are plastic assemblies that clip into the ejector housing and press upward on the bottom of the trigger bar’s cruciform sear plate.

Armorer’s Slide Plate: These are kind of neat, but to be honest I don’t use it often. The plate is cut off at the bottom to allow you to see directly into the guts and observe the sear engagement.

Trigger Connectors: The small folded over shelf of the connector is the actual cam for the trigger bar, so the angle of that shelf plays a large part in determining the weight of the letoff. Here you can see a 3.5# Ghost trigger connector pictured next to the OEM 5.5# Glock trigger connector and compare the angle of the shelf side by side. The little hand sticking up is where the slide cams the connector inward to act as a disconnector. Slide locks and accuracy: There has been a lot of discussion about machined slide locks (note, locks, not slide stops) improving mechanical accuracy on Glock pistols for the past several years. I’ve never been able to verify these claims myself, but if you have issues grabbing that little bugger to take the gun down it wouldn’t hurt to pick up a machined and extended one. Much of what I know about Glocks was learned from T.R. Graham, who pioneered the “match grade slide lock” and still makes them if you contact him.

Slide locks and accuracy: There has been a lot of discussion about machined slide locks (note, locks, not slide stops) improving mechanical accuracy on Glock pistols for the past several years. I’ve never been able to verify these claims myself, but if you have issues grabbing that little bugger to take the gun down it wouldn’t hurt to pick up a machined and extended one. Much of what I know about Glocks was learned from T.R. Graham, who pioneered the “match grade slide lock” and still makes them if you contact him.

Conclusion

Well, the world’s shortest disassembly guide turned into an afternoon project! Despite all of the rambling and commentary, this guide only scratches the surface of a pistol design that has gone from being the ugly duckling of the gun world to a huge aftermarket success. These days you can build a Glock that doesn’t even have Glock parts, using aftermarket slides, frames and barrels from quality names like Lone Wolf, Zev, PWS, BCE, and Fowler. Whether you want to take this old 1994 Glock 21 and tune it up a little bit with only department friendly OEM parts or go nuts turning your Glock into a cerakoted open division race gun, Glocks truly have become a platform for any shooter.

I do tutorials and guides in my free time to give back to the firearm community. Each of these guides takes up to five hours to document, photograph, process, research, draft and format! If you want to help keep content flowing, there are a few ways you can pitch in: Loan me a gun or accessory for review, send me questions or ideas for writeups, donate spare gun parts or simply shop at your friendly neighborhood gunsmith!

If this disassembly guide has been useful or helped you out, please consider a small donation via PayPal.